Operation of the Lighthouse

The construction of the Tower of Hercules has been dated to between the 1st century B.C. and 1st century A.D. It is the only Roman lighthouse that has carried out its original function from its creation through to the present day, maintaining its purpose as a maritime signal and navigational aid for ships crossing this area of the Atlantic corridor.

The Romans chose Punta Eiras as the location for the lighthouse, at the end of the peninsula on which the city of A Coruña was founded. At that time northwestern Spain represented the western limit of the Roman Empire, which made the tower’s construction of vital importance for navigation during that era. According to the more recent research, the light that shone from the lighthouse was fueled by an enormous oil lamp with a perforated stone placed on top. A wick emerged from the hole in the stone, which when lit caused the light to be projected onto a parabolic mirror. This mechanism was also movable thanks to a hydraulic system, which allowed the 7 flashing of the light emitted to be interpreted as a maritime signal.

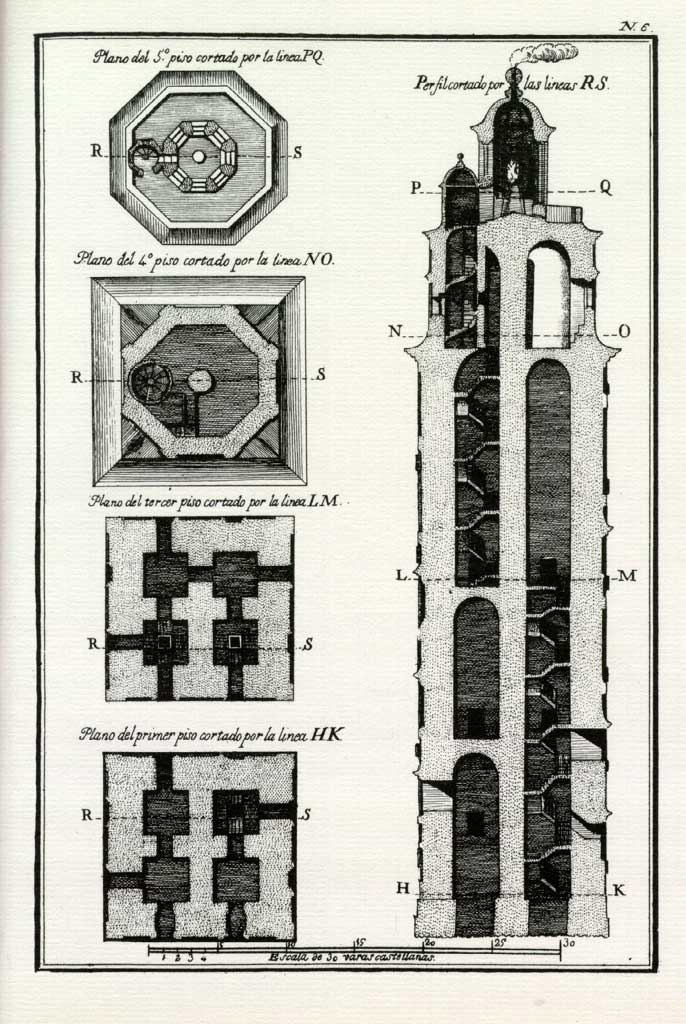

Between the 5th and 15th centuries, various sources indicate that the tower may have served a double purpose, that of a fortress as well as a lighthouse. Prior to the structure’s neoclassical-period alterations, in 1684 an interior stairway was built as well as two small towers with lanterns.

After 1790 the main light was fueled with coal burning in an iron brazier, and was supported by another oil-burning lantern. Further technological improvements to the light system took place throughout the 19th century. After alterations were made to the upper part of the structure, a rotating mechanism was installed in 1806 and the power of the light was increased using a catadioptric system that allowed the light to reach a distance of 20 miles. In 1883 a new mechanical lamp that burned paraffin was installed, with the light now being reflected by 48 panes of glass.

In 1927 the lighthouse went electric and the range of the light was extended up to 32 miles, and 50 years later a continuous-emission radio beacon was installed and four flashes of white light began to be emitted every 20 seconds, which could be seen for 23 miles.

The Tower of Hercules is now the only example of the type of maritime signaling structure built by the Roman Empire and continuing to operate today, either along the shores of the Mediterranean or the Atlantic. However, other important Roman-era lighthouses were constructed along the Atlantic coast, such as the lighthouse in the city of Cadiz in Spain, which is now crowned by a large statue; the nearby Chipiona lighthouse, which was described by the Greek geographer Strabo as one of the major lighthouses of its time; the Tour d’Ordre in France, which once measured 60 meters in height but was buried under a landslide; and the Dover lighthouse in England, constructed on the orders of the emperor Caligula.

On the shores of the Mediterranean, the Ostia lighthouse in Italy signaled the entrance to the empire’s most important port because of its proximity to Rome; the lighthouse in Messina guided maritime traffic between Sicily and the Italian peninsula; the Laodicea lighthouse in Turkey was key in the development of trade links to the east, and the Leptis Magna lighthouse in Libya is part of an archaeological complex that is also registered as a World Heritage Site.